Exploring the potential experience of LGBTQ Christians

Last night I attended the Anscombe society’s panel discussion on “Humanae Vitae” and had the chance to connect with a friend and classmate of mine, Sara Freund, who wrote an article on self-gift and LGBTQ identity for The Cor Chronicle a couple weeks ago. In her article she commented upon the LGBTQ community and how it creates a “new religious system” where people “turn to [themselves] to find [their] identity” instead of seeking their identity in Christ.

It was a poignant article, but I could not help but notice some necessary distinctions that she omitted, such as the role of identity versus ideology, and of course the place for LGBTQ Christians who still ardently seek to live in accord with God’s will.

In the first place it seems necessary to point out that identity is not the same as ideology; to assume that all people in the LGBTQ community share the same philosophical beliefs seems ludicrous. But what Freund aims to do is characterize the ideology that tends to lead to certain beliefs. She pulls from an earlier article written by Mark Regnerus who points out the similarities in belief between non-heterosexual individuals, abortion activists, and supporters of physical transition for gender dysphoria. But a correlation does not infer causation.

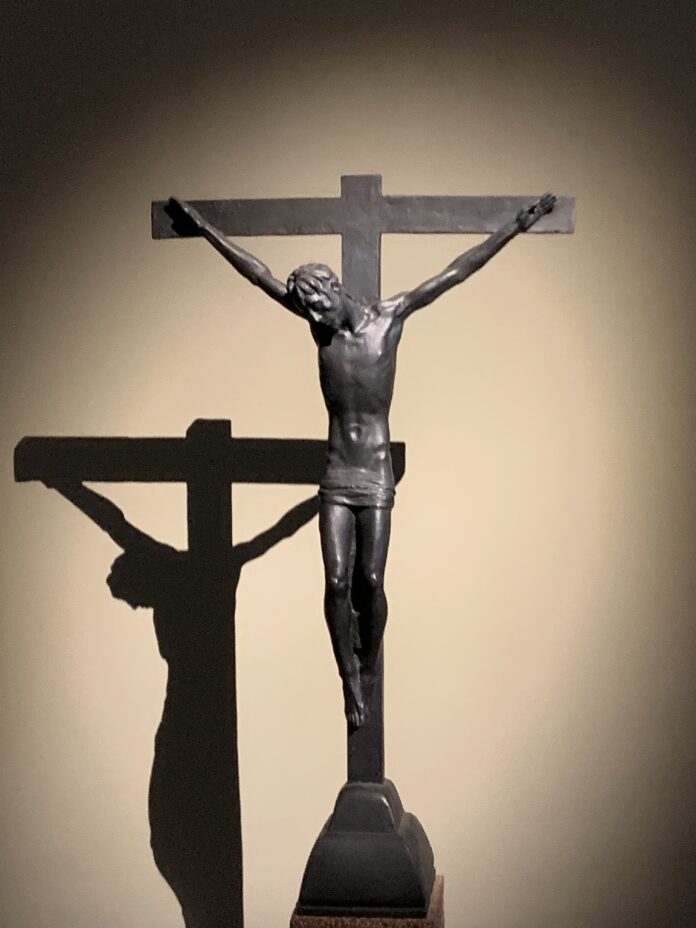

Identity and ideology are not the same thing, and just because someone has a certain identity does not mean that they believe in a certain ideology. Many gay and bisexual Christians struggle with finding their identity, especially when told to find it in Christ if Christ seems to have burdened them with the cross of same-sex attraction.

And yet, this cross is not a curse, nor a burden; it is something that must be accepted in good faith with the knowledge that one’s sexuality is precisely what God intends it to be. Many Christians have heard the argument that being gay or bisexual is not wrong, it’s just acting on those desires that constitutes a sin.

This may be true, but it seems very unsatisfactory to say that God imbues certain people with the extra disposition to sin as a test. A shift of perspective might allow us to see how sexuality can be expressed in chastity, just as we expect from our priests, religious, and even sometimes our married brothers and sisters.

For a group that is already marginalized, it seems all the more important to find a place for gay and bisexual people in the Church or else they will find themselves outside of it. If we believe that every person must find their identity in Christ, then we must at some point accept—and furthermore, embrace—the fact that all of us must find our sexuality in Christ as well.

As Freund points out, there is a sure danger in making yourself your own creator, and turning inward to yourself for identity when you should rightfully find your identity in Christ. But these things may not be necessarily contradictory.

As our favorite Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins so profoundly points out in “As kingfishers catch fire,” every person must find Christ in themselves:

“Acts in God’s eye what in God’s eye he is—

Christ—for Christ plays in ten-thousand places,

Lovely in limbs and lovely and eyes not his

To the father through the features of men’s faces”

We are meant to be what God calls us to be, which is no less than Christ on earth. To search for our identity in Christ is precisely to look inward because we are made in the image of God. Finding our identity in Christ is synonymous with embracing the identity Christ has given us. We cannot in good faith deprive ourselves of any of the aspects of ourselves with which He has individually blessed us.

Now it is important to make the caveat that embracing one’s identity in Christ is not to embrace sin. Whatever capacity for sin that we find in ourselves is a result of the fall, and does not come from Christ. I spoke on this distinction at length in the article I wrote for this publication last year on masculinity, and the same concept applies here.

Yet, in all our brokenness and our capacity for sin, at our core and in our deepest identity, each person is made to be like Christ. As such, we must embrace our entire identity as Christlike.

A well written article indeed. The world needs to know this.