As students of the University of Dallas, we all have taken classes that aim to produce a pointed sense of tradition in our minds. Whether this was a simple Lit Trad I class or any one of the seven classes about the history of Rome, there is no way that you will come out of a UD education without a taste for antiquity.

However, archeology, which aims at uncovering the remnants of antiquity, is a somewhat neglected science in the mind of college students.

To be fair, there are too many archaeological discoveries to name that are made every day. Here are a few that may stand out to us liberal arts students as important from across the world.

Over the summer, some bones were found in Argentina bearing signs of having been cut with stone tools, according to an article by Sci News. These bones date back to 5,000 years before humans were thought to be in that region.

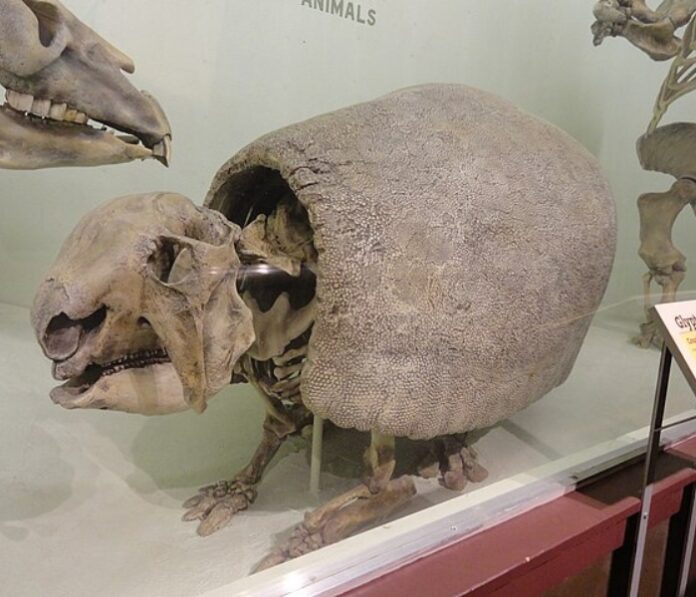

The bones were from a Glyptodon, a massive armadillo-like animal, which went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene epoch some 21,000 years ago.

If it is the case that the animal was killed by stone weapon-bearing humans, then it might reveal that humans were linked with the extinction of the large mammals of the previous era.

It is somewhat speculative that the animal was killed by humans. There are marks consistent with those made by stone tools on some of the bones of the glyptodon.

Since the bones were dated using the radiocarbon dating method, archeologists speculate that humans could have been present in South America around 5,000 years before the earlier estimates.

Another headlining find also occurred over the summer. On the island of Crete, a massive Minoan structure was unearthed at the site of the construction of an international airport, the Smithsonian Magazine reports.

The structure, which dates back to 2000 B.C., resembles a wheel with a few concentric circles. It is speculated that the structure was a place for sacrifices, as the bones at the site suggest.

The structure is 157 feet in diameter and sits atop the Papoura Hill, which is right where the radar station for Crete’s new international airport would be located.

This find may seem rather common and mundane. In reality though, this site has the potential to elucidate much about the ancient people who inhabited Crete and built the great marvels on the island, such as the palace at Knossos.

Moving out of the Mediterranean, two Roman Villas were discovered on the outskirts of a known Roman town in England. This discovery sheds light on the Roman occupation of the area, which is reported by a Popular Mechanics article.

Near the ruins of the town of Wroxeter, which is on the Attingham estate, two Roman villas, a cemetery, farmsteads and a network of roads were all found using a magnetometer survey.

A magnetometer survey is a very precise measurement that uses minute changes in electromagnetic fields to find evidence of human activity buried beneath the earth.

These findings will help archeologists learn more about the Roman occupation in England at large.

The villas have not been uncovered yet, but archeologists are hopeful that once they and the surrounding land are examined, they can piece together the lives of the early inhabitants of the land and their Roman conquerors.

One final interesting finding has been coming along for a decade now. In Uzbekistan, two major cities, Tugunbulak and Tashbulak, were unearthed along the Silk Road, which runs from Florence to China. These cities have changed what we now think about the nature of the Silk Road.

The New York Times reports that Michael Frahetti, the discoverer of these two ancient cities, said that, strangely, they were constructed on the tops of hills. This goes against the previous assumption that the Silk Road stuck to the lowlands for ease of travel.

Using LIDAR technology, Frachetti has slowly been mapping the area. These findings will change what we know about the history and culture of the trade along the Silk Road.

All of these findings are seemingly small in size, but in extremely large in scope and significance.