An enjoyable take on democratic ideals

How are we to understand stereotypes in art and film? To an unpracticed observer, their use is an indication of a lack of originality in a work of fiction, and an over reliance on the audience’s expectations of a stereotypical character to do the heavy lifting of character development. This is certainly true in many cases; but when used skillfully, the subversion of a stereotype can carry a powerful moral to the audience.

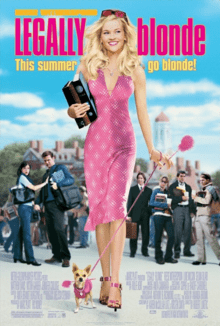

An excellent example of this is “Legally Blonde,” a 2001 “chick flick” that is right at home next to the likes of “Mean Girls,” “Clueless” and “10 Things I Hate About You,” with all the trappings of a “teen girl” movie and standard feminine stereotypes. Pink fur assaults the eyes; a handbag chihuahua has a significant amount of screen time, two textbook beauties engage in a dominance contest over a man.

Yet these early 2000s chick flick tropes are surprisingly and satisfyingly synthesized with a legal drama atmosphere. The contrast of these two worlds serves as a humorous foundation for a story of personal character and competence triumphing over social stigma and prejudice.

The movie begins with a straightforward dress up montage of Elle Woods, college sorority senior, who expects to be proposed to that night by her boyfriend, Warner. At the key moment, he breaks up with her instead, citing his need to be with someone “serious” to accompany his upcoming legal and political career; in Elle’s words, because she’s “too blonde.”

After a week of post breakup mourning, Elle resolves to follow Warner and win him back through an unlikely route: getting into Harvard Law School and training to be a high-octane lawyer. Here is where the moral of the movie begins to shine. Everyone Elle encounters, from her sorority friends to her high-class family, are of the same opinion as Warner that she is not serious, smart or boring enough for a legal career, but all of this bounces off of her bubbly and cheerful demeanor.

Elle is accepted to Harvard on the merit of her academic achievements and personal character, however foreign and unique she may be to the “serious” world of legalism and politics. Throughout the drama of her adjusting and adapting to the environment of Harvard Graduate School, she is villainized, ostracized and discouraged from succeeding by her peers and professors.

Assumptions of high-class prejudice are made against her; her attention to fashion is used to demonize her; and she is deduced to be dimwitted from her sorority mannerisms. Elle summarizes her predicament with the zinger “All people see when they look at me is blonde hair and big boobs.”

Yet Elle is far more than her outer appearance.

Her quick witted and clever responses in class earn her the respect of her professors, getting her a coveted internship working on an active murder trial. Her kind instincts gain her the trust of her defendant, and the movie climaxes with her tricking the true murderer to confess the crime using her knowledge of perms and hair maintenance. She receives glory and praise, and the movie ends with her giving the valedictorian speech of her graduating year.

The story follows a similar arc to many other legends of democracy, in which a person’s innate character and ability overcome the arbitrary obstacles that society places to their success. Think of Abraham Lincoln, a backcountry lawyer who climbs to the top to lead his country, the thousands of examples of immigrants to America whose economic initiative won out against the pressures of poverty or classism, or Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave whose philosophical and political contributions to the American tradition placed him in history next to the greats of the Founding Fathers.

The story of Elle Woods surpassing the expectations of those around her to become something greater than even she thought herself capable carries on this tradition of the democratic ideal — that a person’s measure lies in who they are and not what people think of them — and does so in a spirit of fun and playful humor.