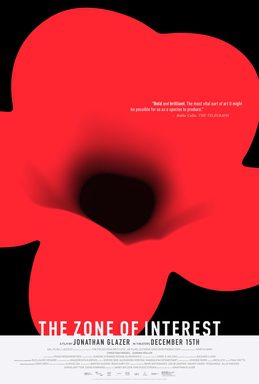

Amidst the hype surrounding many of this year’s Oscar nominees, “The Zone of Interest” lies undetected in multiple categories. This is not entirely because of willful ignorance, as it is a squarely arthouse film whose theatrical release has been tremendously staggered, only reaching a few Dallas theaters nearly two months after its initial release in New York and Los Angeles.

However, “Zone” may also remain lowkey because its subject matter directly clashes with the self-congratulatory air of Hollywood’s biggest night: can a movie about true evil ever be so accepted into the mainstream?

“Zone,” from British director Jonathan Glazer (“Under the Skin,” “Birth”) revolves around the life of Rudolf Höss (Christian Friedel) and his family. He is a generous, involved father to his children and a loving partner to his wife, Hedwig (Sandra Hüller). During the day, he is blessed to have a short commute to the Auschwitz concentration camp, where he serves as commandant.

This contrast is not merely for shock value, but the jumping point of the entire film. “Zone” is a movie built on spatial contrasts; we are focused on the daily life of the Höss family in their well-cleaned house and blooming garden, but one cannot help but notice the smokestacks peeking over the concrete walls in their yard. As birthday celebrations and morning makeup applications play out, something we cannot see, yet know is horribly wrong, is happening right next to them.

Thus goes most of “Zone.” It is likely the most austere movie of the year, with a distanced, largely unmoving camera and a general lack of a score (apart from two haunting soundscapes to open and close the movie, as well as some very brief interludes, from composer Mica Levi). Friedel and Hüller are not gunning for any awards with their performances, instead working with understated naturalism punctuated by a few memorably venomous outbursts.

It may very well have been about nothing if it wasn’t for that which lay behind the walls. A few brief sequences dare to give us the smallest peek into the camp, such as surreal night-vision scenes of a young girl hiding apples for the prisoners, or a shot of Höss at work which ranks as one of the most haunting in recent memory without showing anything besides his face.

We never see the prisoners themselves, but the movie asks us: could we ever see the prisoners if we weren’t there? Could we even dare to water down that evil for an afternoon at the movies?

Just knowing that this family not only runs the camp but dared to build their dreamy lives right next to it poisons every minute action we see, turning something as normal as a family dinner or work call into a part of a twisted black ritual.

“Zone” proceeds as an “un-dramatic” drama, not because of the faults of its makers but because it has intentionally removed the notion of cinematic illusion from itself.

Genocide is contained within the most banal political discussions; when we see “Operation Höss,” the forced deportation and execution of over 400,000 Hungarian Jews, formulated by the Nazi leaders later in the film, it is given the weight of a quarterly budget report. Its understatement could sound disrespectful, but it ends up only being all the more terrifying; it did not take inhuman fanaticism to approve this extermination, but only a human sense of duty.

I don’t know if the “banality of evil” is an idea that I could speak at length on, but “Zone” bets its entire runtime on it; a smarter man than I may disagree, and say that these characters should be presented more ferociously. After all, we are constantly reminded that these people can ignore the depravity they have instigated, but exactly why they do so seems to be ignored.

Still, if reality is anywhere close to the median between rabid hatred and banality, then “Zone” is worthy of its praise. In its plainness lies one of the most unflinching depictions of the Holocaust put to screen, effectively demonstrating its horrors without trying too hard to make you feel them. It only asks us to recognize one terrifying truth: the demons of history weren’t unimaginable caricatures. In fact, they could be someone like us.